Understanding how people make decisions is the cornerstone of ethical influence. Choice architecture shapes environments where individuals naturally gravitate toward beneficial outcomes without coercion or manipulation.

🧠 The Hidden Forces Shaping Every Decision You Make

Every day, you make thousands of decisions, from trivial choices about breakfast to significant commitments affecting your future. What many don’t realize is that the context surrounding these decisions profoundly influences outcomes. This is the realm of choice architecture—the practice of organizing the context in which people make decisions.

The concept gained prominence through the groundbreaking work of behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their influential book “Nudge.” They demonstrated that small, thoughtful changes in how choices are presented can dramatically alter behavior without restricting freedom of choice.

Unlike manipulation or coercion, ethical nudges preserve autonomy while guiding people toward decisions that benefit them and society. The cafeteria that places healthy foods at eye level isn’t forcing anyone to eat salad—it’s simply making the healthier choice more accessible and appealing.

The Psychological Foundation: Why Nudges Work

Human beings are not the perfectly rational decision-makers that classical economics once assumed. We operate with cognitive limitations, biases, and mental shortcuts that influence our choices in predictable ways. Understanding these psychological mechanisms is essential for ethical persuasion.

Cognitive Biases That Shape Our Choices

Status quo bias represents our tendency to stick with current situations rather than change. This explains why default options carry such powerful influence. When organ donation is opt-out rather than opt-in, participation rates skyrocket—not because people’s values changed, but because doing nothing now means staying enrolled.

Loss aversion makes us feel the pain of losing something twice as intensely as the pleasure of gaining something equivalent. Framing a gym membership as “don’t lose your fitness momentum” proves more effective than “gain better health,” even though both statements convey similar information.

Social proof leverages our instinct to follow the crowd. Hotel rooms displaying messages like “75% of guests reuse their towels” achieve better compliance than generic environmental appeals. We constantly look to others for behavioral cues, especially in uncertain situations.

The Two Systems of Thinking

Daniel Kahneman’s research identifies two distinct modes of cognitive processing. System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little effort and no sense of voluntary control. System 2 allocates attention to effortful mental activities that demand concentration.

Most daily decisions rely on System 1 thinking. We don’t carefully analyze every choice—we’d be mentally exhausted by noon. Instead, we use heuristics and intuitive judgments. Effective choice architecture works with System 1, making beneficial choices feel natural and effortless.

However, System 2 remains available when needed. Ethical nudges never hide information or make switching options difficult. The goal is to help System 1 make better automatic choices while keeping System 2 accessible for deliberate consideration.

🎯 Core Principles of Effective Choice Architecture

Building ethical persuasion systems requires adherence to fundamental principles that respect human autonomy while acknowledging cognitive realities. These guidelines ensure that nudges serve people’s genuine interests rather than exploit their vulnerabilities.

Transparency and Disclosure

Never hide the fact that you’re organizing choices intentionally. Transparency builds trust and distinguishes ethical nudges from dark patterns. People should understand that their environment has been designed with specific goals in mind.

Effective disclosure doesn’t require announcing every psychological principle at play—that would be overwhelming and counterproductive. Instead, be clear about your intentions. A retirement savings program might state: “We’ve set your contribution rate at 6% because research shows this helps people reach their goals. You can change this anytime.”

Easy Reversibility

Ethical choice architecture makes opting out as simple as opting in. The power of defaults shouldn’t trap people in unwanted situations. If someone chooses differently than your nudge suggests, that path should be friction-free.

Subscription services that make cancellation deliberately difficult violate this principle. They’re exploiting cognitive biases rather than serving customer interests. Contrast this with platforms that offer one-click unsubscribe options—they trust that their value proposition will retain customers without manipulative barriers.

Alignment with User Interests

The most crucial ethical consideration asks: does this nudge genuinely benefit the person being influenced? Self-interest on the part of the choice architect doesn’t disqualify a nudge, but user benefit must be central.

Automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans benefits both employers (who fulfill fiduciary duties) and employees (who build financial security). This alignment creates sustainable, ethical persuasion. When interests diverge significantly, the design enters ethically murky territory.

Practical Applications Across Different Domains

Choice architecture principles apply across countless contexts, from public policy to product design. Understanding domain-specific applications reveals both the versatility and limitations of ethical nudges.

Health and Wellness Interventions

Healthcare settings offer particularly compelling opportunities for beneficial nudges. Appointment reminder systems with pre-scheduled times reduce no-show rates more effectively than reminders requiring patients to call back. The default action (keeping the appointment) aligns with patient health interests.

Prescription medication packaging designed for better adherence uses physical architecture—blister packs with day labels—to nudge consistent consumption. Patients retain complete freedom to skip doses, but the design makes following through easier.

Cafeteria layouts profoundly influence food choices. Strategic placement of fruits and vegetables, smaller plates that naturally limit portions, and strategic lighting that makes healthy options more appealing all demonstrate physical choice architecture in action.

Financial Decision-Making

Personal finance represents another domain where cognitive biases often work against our long-term interests. Present bias makes us prioritize immediate gratification over future security, while choice overload paralyzes us when faced with too many investment options.

Automatic escalation programs gradually increase retirement contributions as salaries rise. People barely notice the incremental changes, but accumulation effects prove substantial. Participants can opt out anytime, preserving autonomy while leveraging status quo bias beneficially.

Simplified investment options reduce analysis paralysis. Instead of presenting 50 mutual funds, offering three diversified portfolios (conservative, moderate, aggressive) helps people make decisions that might otherwise be indefinitely postponed.

Environmental Sustainability

Energy consumption feedback programs demonstrate social proof in action. When utility bills show how household usage compares to neighbors, consumption typically decreases. The competitive instinct and social comparison drive conservation without mandates or restrictions.

Default settings carry environmental implications. Printers set to double-sided printing by default reduce paper waste dramatically. Users can override for single-sided when needed, but most stick with the eco-friendly default.

Digital Product Design

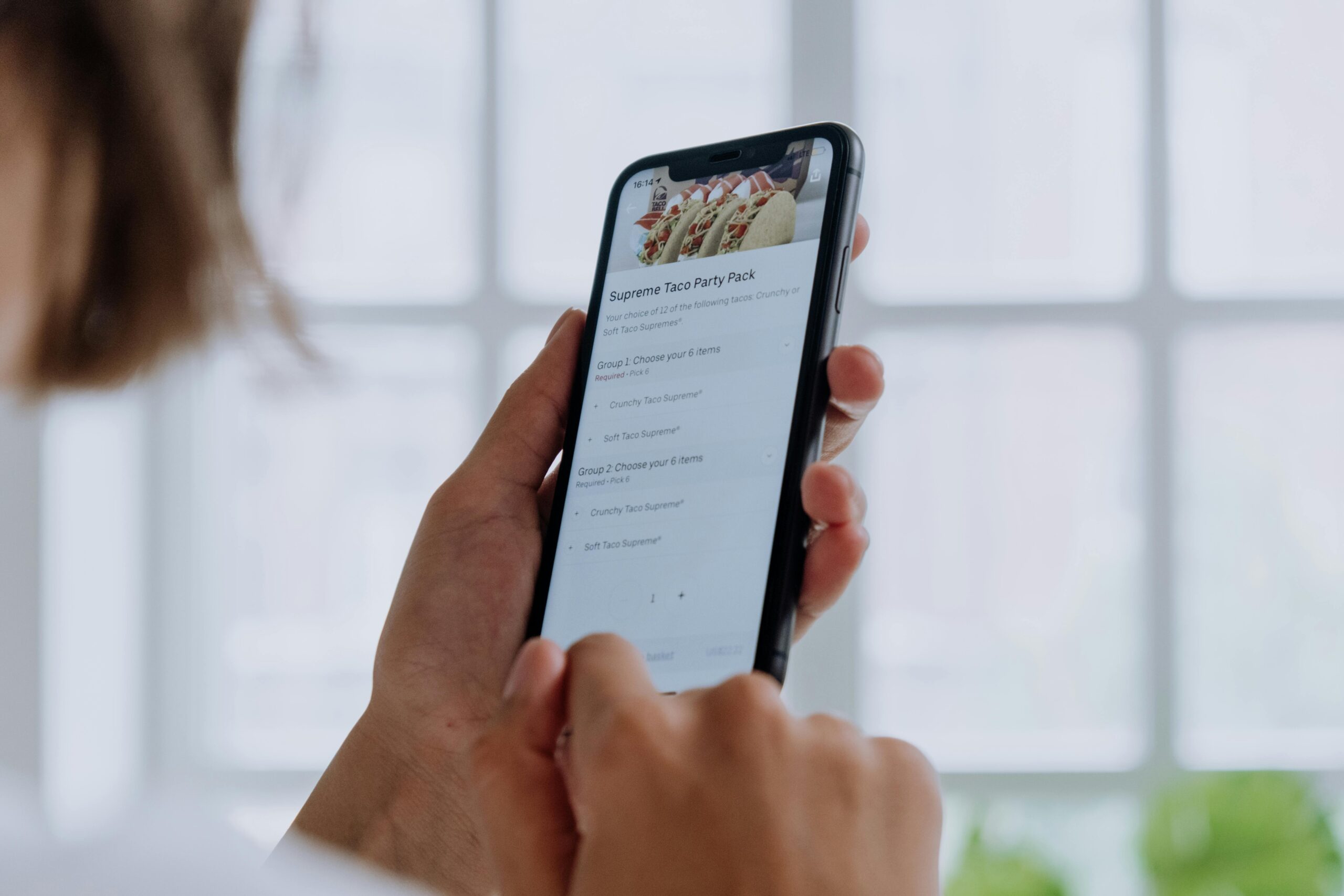

User experience designers constantly apply choice architecture principles, though not always ethically. The distinction between beneficial nudges and manipulative dark patterns becomes particularly important in digital environments.

Privacy settings defaulted to maximum protection serve user interests, even if companies might prefer more data collection. Progressive disclosure that presents complex options gradually rather than overwhelming new users applies choice architecture ethically.

Notification systems demonstrate the ethical spectrum clearly. Thoughtful platforms allow granular control and default to minimal interruptions, respecting attention as a valuable resource. Exploitative platforms maximize engagement through psychological manipulation regardless of user wellbeing.

⚖️ Navigating the Ethical Boundaries

The line between ethical persuasion and manipulation isn’t always obvious. Thoughtful practitioners grapple with nuanced situations where principles potentially conflict or where good intentions might produce unintended consequences.

The Slippery Slope of Paternalism

Critics worry that choice architecture represents a form of soft paternalism—making decisions on behalf of others based on what experts consider best. This concern deserves serious consideration, even when nudges seem obviously beneficial.

The counterargument notes that choice neutrality is impossible. Someone always designs the context for decisions, whether intentionally or accidentally. Random or unconsidered design often produces worse outcomes than thoughtful architecture aligned with user interests.

The key distinction lies in preserving meaningful choice. Ethical nudges acknowledge that complete neutrality is a myth while maintaining genuine freedom to choose differently. They guide without dictating, influence without controlling.

Cultural and Individual Variation

What works as an ethical nudge in one cultural context might feel inappropriate or ineffective in another. Social proof particularly varies across individualistic and collectivist societies, where conformity carries different meanings and values.

Individual differences matter too. Some people respond well to reminders and prompts, while others find them annoying or patronizing. Sophisticated choice architecture accommodates personalization, allowing people to adjust nudge intensity or opt out of specific interventions.

Power Dynamics and Vulnerability

Choice architects typically hold more power and resources than the people they’re nudging. This asymmetry demands additional ethical scrutiny, particularly when influencing vulnerable populations with limited alternatives.

Low-income individuals facing financial choices, patients navigating complex medical decisions, or consumers with limited education all deserve special protection against exploitative nudges. The greater the power imbalance, the higher the ethical standard should be.

🛠️ Designing Your Own Ethical Nudges

Whether you’re a policymaker, product designer, manager, or simply organizing choices in your own life, practical frameworks help ensure ethical application of choice architecture principles.

The NUDGES Framework

This systematic approach provides a mental checklist for ethical persuasion design:

- Notice: Identify specific behavioral patterns you want to influence and why change would be beneficial.

- Understand: Research the psychological factors driving current behavior and potential barriers to change.

- Design: Create interventions aligned with user interests, using appropriate behavioral insights.

- Generate: Implement the nudge with full transparency about your intentions and methods.

- Evaluate: Test effectiveness rigorously and monitor for unintended consequences.

- Sustain: Maintain ethical standards over time as contexts evolve and new information emerges.

Testing and Iteration

Even well-intentioned nudges sometimes produce unexpected results. Rigorous testing before full implementation helps identify problems early. A/B testing allows comparison between different choice architectures and control conditions.

Qualitative feedback complements quantitative metrics. Sometimes behavioral data shows a nudge working exactly as intended, but user interviews reveal frustration or resentment. Both dimensions matter for ethical evaluation.

Iteration acknowledges that initial designs rarely achieve perfection. Continuous improvement based on evidence and feedback demonstrates commitment to genuinely serving user interests rather than imposing predetermined solutions.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced practitioners make mistakes when applying choice architecture. Awareness of common errors helps avoid repeating them in your own work.

Overcomplicating the Intervention

Elegant nudges typically involve simple changes to existing environments. Elaborate systems with multiple components often fail because they introduce new complexities rather than simplifying choices.

Start with the smallest intervention that might work. If placing healthy snacks at eye level succeeds, you don’t need a complex point system, educational campaigns, and personalized recommendations. Simple solutions that work beat sophisticated systems that don’t.

Ignoring Context and Culture

A nudge that succeeds brilliantly in one environment may flop or backfire in another. Cultural assumptions about authority, community, health, and autonomy all influence how people respond to different persuasion approaches.

Local testing and contextual adaptation prove essential. Rather than importing solutions wholesale from different settings, understand the specific psychological and cultural dynamics of your target environment.

Confusing Nudges with Mandates

Sometimes policymakers or managers implement what they call nudges but are actually requirements disguised with friendly language. If people can’t easily choose differently, it’s not a nudge—it’s a mandate that might be justified but shouldn’t be mislabeled.

True choice architecture preserves genuine alternatives. Transparency about when you’re mandating versus nudging maintains trust and credibility.

🌟 The Future of Ethical Persuasion

As behavioral science advances and digital technologies enable increasingly sophisticated interventions, the importance of ethical frameworks grows correspondingly. Several emerging trends will shape how choice architecture evolves.

Artificial Intelligence and Personalization

Machine learning enables hyper-personalized nudges tailored to individual psychology, preferences, and contexts. This power amplifies both beneficial possibilities and ethical risks. AI systems might discover persuasion techniques so effective they border on manipulation.

Governance frameworks must evolve alongside technological capabilities. Transparency becomes more challenging when algorithms make millions of micro-decisions about choice presentation. New forms of accountability and oversight will be necessary.

Empowering User Control

The most promising future direction involves giving people more control over how they’re nudged. Imagine systems where you specify your goals and preferred persuasion styles, then receive customized support aligned with your values and preferences.

This collaborative approach respects autonomy more fully than traditional expert-designed interventions. Rather than architects deciding what’s best for users, the relationship becomes more partnership-oriented.

Transforming Good Intentions into Better Outcomes

Mastering subtle persuasion through ethical choice architecture represents a powerful tool for improving individual and collective wellbeing. The techniques discussed throughout this article work precisely because they respect human psychology rather than fighting against it.

The responsibility accompanying this power cannot be overstated. Every choice architect—whether explicitly trained in behavioral science or simply organizing options for others—shapes outcomes that matter for real people’s lives.

Success requires constant vigilance against the temptation to exploit cognitive biases for personal gain at others’ expense. It demands humility about the limits of expertise and willingness to adjust when evidence suggests better approaches. Most fundamentally, it requires genuine commitment to serving the interests of those being influenced.

When applied ethically and thoughtfully, choice architecture doesn’t manipulate or diminish human agency. Instead, it acknowledges the reality that contexts always influence decisions, then takes responsibility for designing those contexts well. The result is environments where beneficial choices feel natural, effortless, and genuinely chosen.

The art of subtle persuasion, practiced ethically, enriches rather than diminishes human flourishing. It represents behavioral science at its best—insights about how we actually think and decide, applied with wisdom and care to help us become who we aspire to be. 🎯

Toni Santos is a user experience designer and ethical interaction strategist specializing in friction-aware UX patterns, motivation alignment systems, non-manipulative nudges, and transparency-first design. Through an interdisciplinary and human-centered lens, Toni investigates how digital products can respect user autonomy while guiding meaningful action — across interfaces, behaviors, and choice architectures. His work is grounded in a fascination with interfaces not only as visual systems, but as carriers of intent and influence. From friction-aware interaction models to ethical nudging and transparent design systems, Toni uncovers the strategic and ethical tools through which designers can build trust and align user motivation without manipulation. With a background in behavioral design and interaction ethics, Toni blends usability research with value-driven frameworks to reveal how interfaces can honor user agency, support informed decisions, and build authentic engagement. As the creative mind behind melxarion, Toni curates design patterns, ethical interaction studies, and transparency frameworks that restore the balance between business goals, user needs, and respect for autonomy. His work is a tribute to: The intentional design of Friction-Aware UX Patterns The respectful shaping of Motivation Alignment Systems The ethical application of Non-Manipulative Nudges The honest communication of Transparency-First Design Principles Whether you're a product designer, behavioral strategist, or curious builder of ethical digital experiences, Toni invites you to explore the principled foundations of user-centered design — one pattern, one choice, one honest interaction at a time.