Persuasion transcends borders, but its effectiveness varies dramatically across cultures. Understanding these nuances can transform how organizations influence behavior globally.

🌍 The Global Language of Nudges

Behavioral economics has revolutionized how we think about decision-making, with “nudges” emerging as a powerful tool for guiding choices without restricting freedom. These subtle interventions—from default options to social proof messaging—have proven remarkably effective in contexts ranging from retirement savings to organ donation. However, a critical question remains largely unexplored: do nudges work the same way across different cultures?

The answer is increasingly clear: they don’t. What motivates behavioral change in Tokyo may fall flat in Toronto, and what resonates in Berlin might backfire in Bangkok. As organizations expand their reach globally, understanding these cultural variances isn’t just academic—it’s essential for effective implementation.

The Foundation: What Makes Nudges Work

Before diving into cultural differences, we need to understand what makes nudges effective in the first place. Nudge theory, popularized by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, leverages predictable patterns in human decision-making. These interventions work by addressing cognitive biases, reducing friction, and making desired behaviors easier or more attractive.

Traditional nudges operate on several key principles. They simplify complex choices, leverage social norms, use strategic defaults, provide timely reminders, and frame information in compelling ways. Each of these mechanisms taps into fundamental aspects of human psychology—but human psychology isn’t uniform across cultures.

The Cultural Dimension Challenge

Geert Hofstede’s groundbreaking research identified six dimensions of national culture that profoundly influence behavior: power distance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term versus short-term orientation, and indulgence versus restraint. These dimensions create distinct psychological landscapes that shape how people perceive and respond to persuasive attempts.

Consider individualism versus collectivism—perhaps the most studied cultural dimension. In individualistic societies like the United States or Australia, people prioritize personal goals, autonomy, and self-expression. Collectivist cultures such as Japan or Indonesia emphasize group harmony, interdependence, and social obligations. This fundamental difference creates divergent responses to the same nudge strategies.

📊 Social Proof Across Borders

Social proof—the psychological phenomenon where people look to others’ behavior to guide their own actions—is one of the most powerful nudging mechanisms. But its effectiveness varies dramatically based on cultural context.

Research demonstrates that social norm messaging works exceptionally well in collectivist cultures. When Japanese hotel guests were told that “most guests reuse their towels,” compliance rates soared. The message aligned perfectly with cultural values emphasizing conformity and social harmony. People in these societies are acutely attuned to group behavior and feel genuine motivation to align with majority practices.

Conversely, in highly individualistic cultures, social proof can sometimes trigger reactance—a psychological response where people resist being influenced because they perceive threats to their autonomy. Americans might think, “Just because everyone else does it doesn’t mean I should.” The same message that drives behavior change in Tokyo might be less effective in Texas.

Crafting Culturally Appropriate Social Messages

The solution isn’t abandoning social proof in individualistic cultures but adapting the framing. Instead of emphasizing what “most people” do, effective nudges in these contexts highlight how the behavior aligns with personal values or provides individual benefits. Messages like “Join forward-thinking individuals who are making a difference” can be more persuasive than simple conformity appeals.

Similarly, the reference group matters enormously. In cultures with high power distance—where hierarchical relationships are respected—social proof from authority figures or high-status individuals carries tremendous weight. In low power distance cultures like Denmark or New Zealand, peer-to-peer social proof may be more influential than top-down endorsements.

⚙️ Default Settings and Decision Architecture

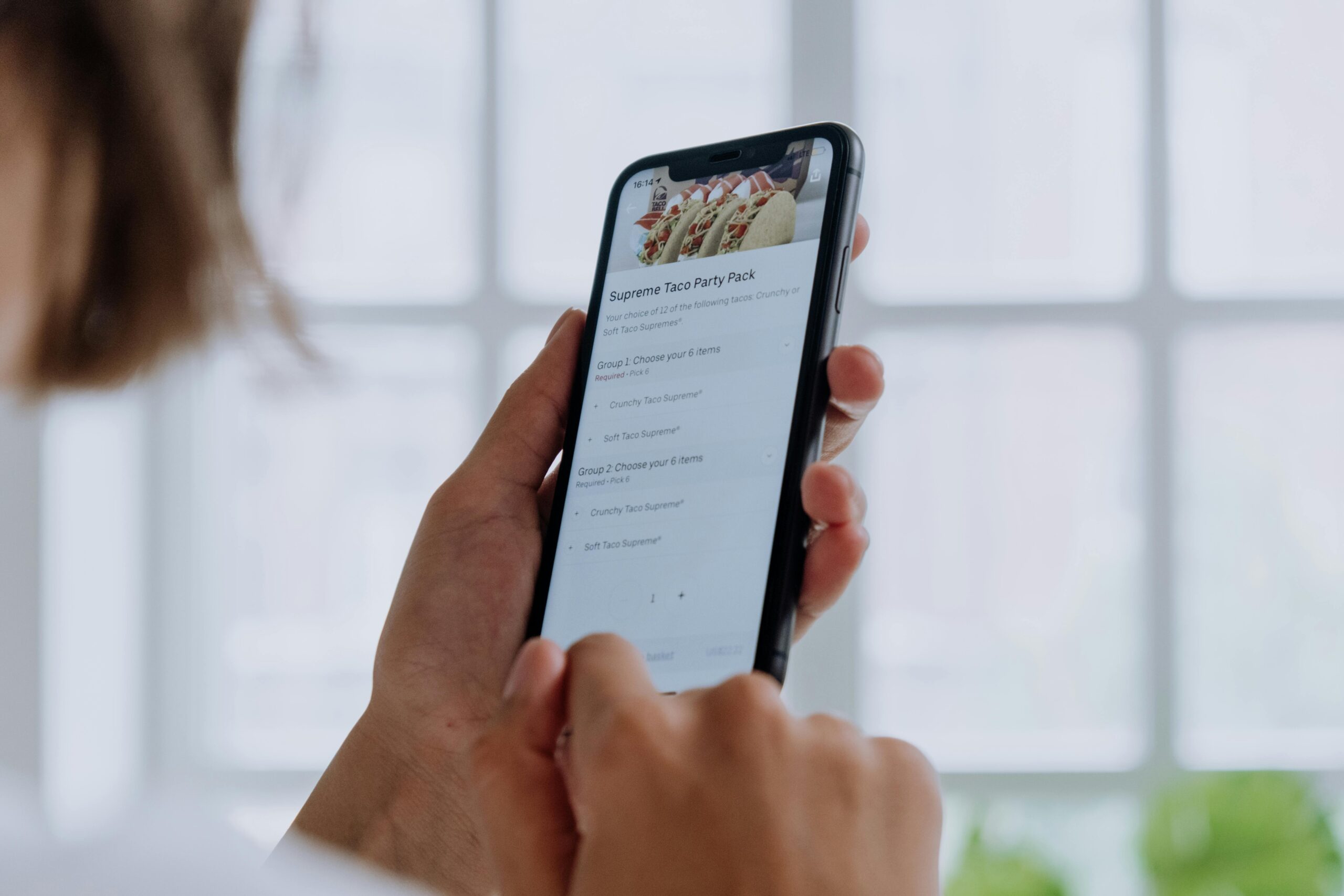

Default options represent perhaps the most powerful nudge tool available. By making a particular choice the path of least resistance, defaults can dramatically shift behavior without eliminating freedom of choice. Automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans, for instance, has revolutionized participation rates.

However, cultural attitudes toward defaults reveal fascinating patterns. Research shows that people in individualistic, low power distance cultures are more likely to actively override defaults they disagree with. They view defaults as suggestions rather than implicit recommendations, feeling comfortable asserting their preferences.

In contrast, individuals from collectivist or high power distance cultures often interpret defaults as carrying implicit social endorsement or expert recommendation. They’re less likely to override defaults, viewing them as reflecting what they “should” do or what authorities recommend. This makes defaults even more powerful in these contexts—but also raises important ethical considerations about manipulation.

The Trust Factor in Default Acceptance

Cultural differences in institutional trust profoundly affect default effectiveness. Scandinavian countries with high levels of social trust show greater acceptance of government-imposed defaults. People assume these choices reflect genuine concern for public welfare. In societies with lower institutional trust, the same defaults might trigger suspicion about hidden agendas or government overreach.

Organizations must consider these trust dynamics when implementing defaults across markets. What works in Stockholm requires careful adaptation for São Paulo, accounting for different baseline assumptions about institutional motivations and competence.

🎯 Framing Effects and Cultural Values

How information is presented—whether emphasizing gains or losses, opportunities or risks—significantly influences decisions. Classic research shows that people are generally loss-averse, responding more strongly to potential losses than equivalent gains. But culture shapes the magnitude and even direction of these effects.

In uncertainty-avoidant cultures like Greece or Japan, loss-framed messages prove particularly powerful. These societies have lower tolerance for ambiguity and risk, making loss prevention a compelling motivator. A message emphasizing “Don’t miss out on protecting your family” resonates strongly, tapping into existing cultural anxieties about uncertainty.

Meanwhile, cultures lower in uncertainty avoidance and higher in indulgence—such as Sweden or the Netherlands—may respond better to gain-framed, opportunity-focused messaging. “Discover new possibilities” appeals to cultural comfort with risk-taking and pursuit of personal fulfillment.

Temporal Framing Across Time Orientations

Long-term versus short-term cultural orientation creates another framing consideration. East Asian cultures typically exhibit stronger long-term orientation, with greater willingness to delay gratification for future benefits. Nudges emphasizing long-term consequences, legacy, and sustainability align with these values.

Short-term oriented cultures respond better to messages emphasizing immediate benefits, quick results, and present-focused rewards. A savings campaign in China might effectively emphasize “securing your grandchildren’s future,” while the same campaign in the United States might perform better highlighting “achieving financial freedom sooner than you think.”

💡 Autonomy, Agency, and Cultural Self-Concepts

Perhaps the most fundamental cultural variance affecting nudge perception involves concepts of self and autonomy. Western psychology has long emphasized the independent self—autonomous, unique, and self-directed. This model underlies much behavioral economics research and nudge design.

However, many cultures operate from an interdependent self-concept, where identity is fundamentally relational and situational. This isn’t simply about collectivism but about how people understand their own agency and decision-making authority.

Nudges that emphasize personal choice and individual empowerment align perfectly with independent self-construals. Messages like “Take control of your health” or “Make your own impact” resonate in contexts where autonomy is paramount. These same messages may feel disconnected or even inappropriate in cultures with interdependent self-concepts, where decisions are understood as inherently social and relational.

Family-Oriented Versus Individual-Oriented Nudges

Practical applications of this cultural difference abound. Health interventions in Western contexts often focus on individual outcomes: your health, your body, your choices. The same interventions in Latin American or Asian contexts often prove more effective when framed around family impact: keeping you healthy for your children, fulfilling your role for aging parents, contributing to household wellbeing.

Financial nudges demonstrate similar patterns. Individual retirement accounts and personal wealth building resonate in individualistic cultures. Collective savings mechanisms, family financial planning, and intergenerational wealth preservation align better with interdependent cultural values.

🔍 Transparency, Ethics, and Cultural Expectations

The ethical dimensions of nudging—particularly around transparency and consent—also show cultural variation. Some argue that ethical nudging requires explicit disclosure of persuasive intent. Others contend that nudges are ethically acceptable when they genuinely serve people’s interests, even without explicit disclosure.

Cultural attitudes toward these questions vary significantly. Low power distance, individualistic cultures tend to demand greater transparency and explicit consent for persuasive interventions. People expect to understand how and why they’re being influenced, viewing this transparency as respecting their autonomy.

Higher power distance cultures may have different expectations. When institutions or experts implement nudges, people may assume benevolent intent and view transparency demands as implying distrust of legitimate authority. What feels like ethical necessity in one context might seem like unnecessary skepticism in another.

Building Cross-Cultural Ethical Frameworks

Organizations operating globally need ethical frameworks that respect cultural diversity while maintaining core principles. This might involve variable transparency approaches—extensive disclosure in contexts that demand it, while focusing on outcome legitimacy in cultures where process transparency is less culturally salient.

The key is avoiding ethical relativism while recognizing that universal principles can be enacted differently across contexts. Respecting autonomy looks different in Tokyo and Toronto, but both approaches can genuinely honor human dignity and freedom.

🌐 Practical Implementation Strategies

Understanding cultural variances in nudge perception is valuable only when translated into practical implementation strategies. Organizations must move beyond universal nudge approaches toward culturally adaptive behavioral design.

First, conduct thorough cultural research before implementing behavioral interventions. This goes beyond demographic data to understanding underlying values, decision-making norms, and institutional relationships. Ethnographic research, local partnerships, and pilot testing prove invaluable for avoiding costly missteps.

Second, develop culturally customized nudge variations rather than simply translating universal approaches. This might mean completely different intervention designs for different markets, not just linguistic translation but fundamental reconceptualization based on local psychology.

Building Cultural Intelligence in Behavioral Teams

Organizations should invest in cultural intelligence training for behavioral science teams. Understanding Hofstede’s dimensions, familiarity with cross-cultural psychology research, and developing cultural humility enable more effective intervention design. Including team members from target cultures in design processes brings invaluable insider perspectives.

Testing and iteration become even more critical in cross-cultural contexts. What works in headquarters might fail abroad, and initial results may surprise. Building robust feedback loops, measuring actual behavioral outcomes rather than assuming effectiveness, and remaining willing to fundamentally revise approaches separate successful global programs from failed transplantation attempts.

📈 Measuring Success Across Cultural Contexts

Success metrics themselves require cultural consideration. Western behavioral interventions often measure individual behavioral change rates, personal outcomes, and individual-level metrics. These measures may miss important outcomes in collectivist contexts, where group-level changes, relationship improvements, or community impacts matter more.

Additionally, timeframes for success may vary culturally. Short-term oriented cultures expect rapid results, making quick wins important for perceived success. Long-term oriented cultures may be more patient, evaluating interventions over extended periods and valuing sustained behavioral shifts over immediate spikes.

Qualitative feedback mechanisms prove essential for understanding not just whether nudges work but how they’re perceived and experienced. Focus groups, interviews, and open-ended feedback reveal cultural reception that quantitative metrics alone cannot capture.

🚀 The Future of Culturally Intelligent Nudging

As behavioral science matures globally, we’re moving toward more sophisticated, culturally intelligent approaches to persuasion and behavioral change. This evolution recognizes that effective influence requires deep cultural understanding, not just psychological insight.

Technology creates new possibilities for personalization at scale, potentially allowing behavioral interventions that adapt not just to individual preferences but to cultural contexts. Machine learning algorithms could identify culturally resonant framing, optimal reference groups, and effective messaging strategies specific to cultural segments.

However, technology also risks amplifying cultural insensitivity if designers aren’t mindful of underlying assumptions. Global platforms must resist the temptation to export Western behavioral models universally, instead building genuinely inclusive design processes that center diverse cultural perspectives from inception.

The organizations that succeed in global behavioral influence will be those that view cultural diversity not as an obstacle to overcome but as an opportunity to develop richer, more nuanced understanding of human decision-making. By unlocking the power of culturally intelligent persuasion, they’ll create interventions that truly serve diverse populations while respecting the beautiful complexity of human cultural expression.

The future of nudging is not universal but pluralistic—recognizing that there are many ways to be human, make decisions, and respond to influence. By embracing this diversity, we unlock persuasion’s true potential to improve wellbeing across all cultural contexts. 🌟

Toni Santos is a user experience designer and ethical interaction strategist specializing in friction-aware UX patterns, motivation alignment systems, non-manipulative nudges, and transparency-first design. Through an interdisciplinary and human-centered lens, Toni investigates how digital products can respect user autonomy while guiding meaningful action — across interfaces, behaviors, and choice architectures. His work is grounded in a fascination with interfaces not only as visual systems, but as carriers of intent and influence. From friction-aware interaction models to ethical nudging and transparent design systems, Toni uncovers the strategic and ethical tools through which designers can build trust and align user motivation without manipulation. With a background in behavioral design and interaction ethics, Toni blends usability research with value-driven frameworks to reveal how interfaces can honor user agency, support informed decisions, and build authentic engagement. As the creative mind behind melxarion, Toni curates design patterns, ethical interaction studies, and transparency frameworks that restore the balance between business goals, user needs, and respect for autonomy. His work is a tribute to: The intentional design of Friction-Aware UX Patterns The respectful shaping of Motivation Alignment Systems The ethical application of Non-Manipulative Nudges The honest communication of Transparency-First Design Principles Whether you're a product designer, behavioral strategist, or curious builder of ethical digital experiences, Toni invites you to explore the principled foundations of user-centered design — one pattern, one choice, one honest interaction at a time.